CS 142 Project 4: Triwizard Tournament Maze

- Demo

- Starter code

- Concepts in this program

- Implementing the project

- Sample output

- Final reminders

- What to turn in

- Reminders

- Challenges

In Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Harry and three other students participate in the Triwizard Tournament, which culminates in having to navigate a large maze, searching for the Triwizard Cup hidden inside. Harry knows that there are many dangers hidden in the maze, so he would like to find the quickest route from his starting location to wherever the cup is hidden, to minimize the amount of time he actually spends inside the maze. To help him, he decides to send his patronus* into the maze ahead of him, while he waits at the start of the maze. The patronus will explore the maze and through a process called backtracking, discover the shortest path from Harry’s location to the cup.

*In the Harry Potter series, a patronus is a spirit or apparition that a witch or wizard can cast. You don’t have to know anything specific about them, or other facts about Harry Potter, other than the patronus is the character that is moving around the maze and determining the shortest path in this project.

In this project, you will write a program to open a text file containing a description of a maze, use a recursive algorithm to discover the fastest way through the maze to the Triwizard Cup, and print out the solution at the end, along with some other statistics.

Demo

Starter code

Make sure you create the project in a place on your computer where you can find it! I suggest making a new subfolder in your CS 142 projects folder.

You can download the starter code for this assignment by creating a new IntelliJ project from version control (VCS) and using the following URL:

https://github.com/pkirlin/cs142-f21-proj4

Concepts in this program

Maze text files

Each text file describing a maze is organized into lines. The first line of each file always contains two integers: the number of rows in the maze and the number of columns. Each of the following lines will contain a single string, representing a single row of the maze.

Here is an example file (maze0.txt):

5 4

####

# ##

# C#

#H##

####

This file describes a 5-row, 4-column maze, though a maze may have any number of rows and any number of columns. The hash marks (#) specify hedges in the maze that the patronus cannot go through; it is guaranteed that there will always be a complete hedge border on the outer boundary of the maze file (so the patronus cannot leave the boundaries of the maze). Harry’s starting position in the maze is specified by the letter H, and the Triwizard Cup that Harry (and the patronus) is seeking is marked by the letter C. Blank spaces specify open sections of the maze where the patronus is allowed to move as it searches for the cup.

Backtracking

We will explore two different recursive formulations of finding the shortest path through the maze, which we will refer to as solving the maze. Both formulations, however, use a concept called backtracking, which is a common computational technique used in situations where we must construct a solution to a problem incrementally piece-by-piece. Often during this process we will have a number of candidate pieces that might work in the solution, but we don’t know ahead of time which ones will work and which ones won’t. So we try all of them one at a time. If we encounter a situation where it is clear our current partial solution is not going to pan out, then we will backtrack to try a new solution.

This technique is often used when people try to solve a jigsaw puzzle. Imagine a large section of the puzzle that is already completed, and we try to fit new individual puzzle pieces into the whole puzzle. If a piece doesn’t fit, we remove it (backtrack) and try another piece in its place. Eventually the entire puzzle is completed.

Backtracking can be used to solve many interesting problems, including puzzles like mazes, but also optimization problems that occur in the real world such as matching medical students to residency training programs, determining airline routes, scheduling work shifts, or deciding where to place a group of new stores in a city. Backtracking is often used in a recursive fashion, because recursion automatically backtracks when it reaches the base case. If you are interested, you can read more about backtracking on Wikipedia.

Recursive formulations

We will develop two recursive formulations to solve a maze. They both use the same idea, but return slightly different kinds of answers. In our first formulation, we will simply determine whether or not the maze can be solved. In other words, this is a boolean (yes/no, true/false) question. Is there a path from Harry to the cup at all?

In the second formulation, we will determine the actual route that Harry can take from his starting location to the cup (sometimes called a path). The route will be a sequence of north/south/east/west directions, indicating the precise sequence of steps Harry must take in the maze.

The recursive functions we will design around these formulations will be based on the current location of the patronus in the maze (a specific row and column).

The base case in both formulations is when the patronus is located at the same place as the cup. At this point, the cup is found, so we know there is a way for Harry to get from his starting location to the cup.

The recursive case in both formulations is similar. The idea is that if the patronus is not located exactly where the cup is, then there are four possible ways to continue solving the maze, each one involving a recursive call:

- Is there a solution to the maze from one step north from the patronus’s current location?

- Is there a solution to the maze from one step south from the patronus’s current location?

- Is there a solution to the maze from one step east from the patronus’s current location?

- Is there a solution to the maze from one step west from the patronus’s current location?

The idea is to make (up to) four recursive calls, from each of the four squares of the maze surrounding the patronus’s current location. Not all four of these calls will be “legal,” in that one or more of the four squares might be blocked by hedges,

Formulation 1: Can the maze be solved? In our first formulation, the patronus must simply determine if the maze can be solved. Here, we don’t care about the path taken from the starting position to the cup’s position.

To solve this problem, the patronus says, “Am I currently located where the cup is located?” (the base case). If so, then we are done (success!). If the patronus is not located where the cup is, it will try to take one step north, and try to solve the maze recursively from that new location. If that didn’t work, it will try to take one step south, and try to solve the maze recursively from that location. It will do the same thing for east and west. If one of those four recursive cases succeeds in solving the maze, then we is done (also success!). If none of the recursive cases solves the maze, then we is done (but with failure).

[ See an example of how the recursive formulation works on a sample maze. ]

Formulation 2: What are the precise steps to solve the maze? The first formulation works, but the problem is is only returns success or failure, not the path taken through the maze.

To remedy this, let’s change our recursive formulation to return strings rather than success or failure. Each string will represent the path through the maze from the starting location to the cup: we’ll use “N”, “S”, “E”, and “W” for the four cardinal directions, and “C” for the cup. If a path can’t be found, we’ll use “X” for failure.

[ See an example of how the recursive formulation works on a sample maze. ]

Your program will implement both recursive formulations.

Breadcrumbs

We will use “breadcrumbs” for marking what squares in the maze the patronus has already visited. The patronus, when moving onto a square of the maze, will drop a (virtual) breadcrumb, marking that square as visited. When the patronus is evaluating its surrounding directions to recurse on, it must make sure never to recurse on a square of the maze with a breadcrumb in it. This will prevent it from walking in circles.

A breadcrumb is placed in a square at the beginning of each recursive function. It is only removed if we reach a dead end, and therefore, when the algorithm finds the cup, we can be guaranteed that there will be a single trail of breadcrumbs from start to finish. In your code, you will represent breadcrumbs by a period character '.'. When the code asks you to drop a breadcrumb, you will literally alter the current character in the maze from a blank space to a lowercase period. If the patronus determines that the recursion fails in all four possible directions, the breadcrumb will be picked back up (turned back into a blank character).

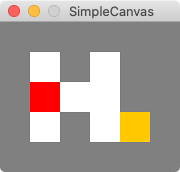

Drawing the maze

The maze will be drawn in a similar fashion to previous projects that used grids (gumdrop gatherer, tic-tac-toe, car racing), in that each square of the maze will be drawn as a square on the board with various features. The exact drawing specifications are up to you, but here are the requirements:

- Pick different colors for the hedges, the open squares of the maze, the location of the cup, and Harry/the patronus’s starting location. I used (gray, white, orange, and red for these, respectively).

- The patronus and breadcrumbs can be drawn either as squares or as dots on squares. I think dots look nicer, but pick whichever you like more.

Implementing the project

For this project, I will provide guidance in terms of a suggested order of writing different parts of the project, but you will have to make more design decisions about what functions and variables to use. There may be times when you want to adjust the public/private-ness of methods, or add more parameters. This is ok.

Begin by getting acquainted with the code. Unlike the previous project, this one only uses two main classes (plus SimpleCanvas).

Maze.java: TheMazeclass is the heart of the project. It represents the current state of the maze, and includes methods to load a maze from a text file, print the maze (in text form), draw the maze on a canvas, and solve the maze in two different ways.RunTournament.java: This class is just a “driver” class for the Maze; it is equivalent to other classes we’ve looked at with “Demo” in their name. It solely exists to get the project started from amain()method, and also contains testing code that you will fill in.

Also take a look at the text files you are provided. Notice how each file begins with a line with the dimensions of the maze (rows & columns), followed by the contents of the maze itself. Remember: # is a wall (hedge) of the maze, a space is an open square in the maze, H is where Harry begins, and C is the location of the cup (the end of the maze). Each maze is solvable except maze3-broken.txt, which is purposefully unsolvable.

Step 1: Decide on instance variables for your maze

Before you can start writing code, you must decide how to store what the maze looks like. This can be done in various ways, such as with a 2-d array of chars, or an array or ArrayList of Strings, or even an ArrayList of ArrayList of Characters (2-d ArrayList). Add appropriate instance variables to the Maze class to store the contents of the maze itself (what you read from the textfile). You will probably want to add variables to store the dimensions of the maze as well.

Note: I think the easiest option is char[][] for the data type of the maze, because then you can use the gumdrop program as a model for many of the algorithms you will write here. Using char[][] makes the file-reading code a little trickier, but I think makes the remainder of the program more straightforward. Using an ArrayList<String> makes it easier to write the file-reading code, but then accessing characters within the maze requires two method calls (one to get() and one to charAt(). Furthermore, when you must modify the maze to drop breadcrumbs, this requires replacing the entire row of the maze, since in Java you can’t modify individual characters within strings.)

Step 2: Reading a maze from a text file

The first piece you will want to get working is reading the maze from a text file.

- There is a function called loadMaze() in Maze.java that takes a string — the name of a text file — as a parameter. What I suggest doing is next is either modifying the constructor for Maze so it also takes a filename String parameter, and then inside the constructor, you can call loadMaze(), passing in that string as the name of the text file. Or, you can forget the constructor, and turn loadMaze() into a public function, and call it yourself. There are comments in the function to help you along, but the idea is you should read the text file and store its contents into whatever variables you created in Step 1.

- Stop and test. Write the testFileReading() function in RunTournament. I suggest having the function create a new Maze object, then loading one of the sample text files (you can either keep changing the function to try multiple files, or you can make a Scanner to have the user type it in. This is just testing code so it doesn’t matter too much.) Depending on how choices you made above, you may need to call loadMaze() yourself, or the constructor will call it for you. Use print statements in your loadMaze() function to print out the file as it’s being read, and make sure everything is working correctly.

- Write the printMaze() function in Maze next. This function is mostly used for debugging, but like in the gumdrop program, it’s important to be able to see the contents of the maze textually.

- Stop and test. Write some additional code in testFileReading() to print out the maze after it was read from the file using your printMaze() function.

Step 3: Drawing the maze with and without the patronus

Next we will focus on the two functions in Maze called drawMaze() and drawMazeWithPatronus(). They do the same basic task — draw the maze — but because the patronus is not represented in the maze itself (it is not a character like H or C), it needs the separate parameters that drawMazeWithPatronus() has.

- The Maze constructor opens a SimpleCanvas, but its width and height are initially zero. Modify these dimensions to make the width and height of the canvas be based on the size of the maze you read in. Depending on how you wrote loadMaze(), you might need to move the call to the SimpleCanvas constructor and the call to show() to the end of loadMaze() if the Maze constructor doesn’t automatically call loadMaze().

- Hint: Like in tic-tac-toe and the gumdrop program, you will need to choose how big the squares are drawn on the canvas. I suggest 30-by-30.

- Fill in the code for drawMaze(). I suggest using your gumdrop program and/or tic-tac-toe as a guide, because the concepts are identical. Follow the guidelines above for drawing hedges, open squares, the cup, and Harry’s starting position.

- Stop and test. Write the testDrawing() function in RunTournament. This test function should read in a maze file and then call drawMaze() so it will be seen on the canvas.

- Examples: maze0.txt

maze1.txt

maze2.txt

- Fill in the code for drawMazeWithPatronus(). This function will be very short, because all you need to do is call your drawMaze() function and then draw a dot for where the patronus is.

- Stop and test. Write the testDrawingPatronus() function in RunTournament. This test function should read in a maze file and then call drawMazeWithPatronus() so it will be seen on the canvas. Note that the maze doesn’t specify where the patronus is, so you should make up some test coordinates for where it is.

- Example: maze1.txt with patronus at row 1, col 2:

- Note: If you cannot get the drawing code to work, you can still proceed to the following steps, using your printMaze() function instead of drawMaze().

Step 4: Get the boolean solver working

In this step, we will write the first recursive formulation of the problem, which determines if the maze can be solved. This is done by implementing the functions canSolve() and canSolve(int patronusRow, int patronusCol). The first of these is the public function that you will call from RunTournament, but the work actually happens in the second, private function which takes the position of the patronus as arguments.

- Write the no-argument canSolve() first. Follow the guidelines in the code. Don’t worry about the second canSolve() function yet.

- Stop and test. This is to verify that you’ve found Harry’s location (the initial location for the patronus correctly). Fill in testBooleanSolver() in RunTournament. Make a simple test function that loads a maze and calls canSolve() (which won’t do much yet). Have canSolve() print out Harry’s location. Verify it is correct.

- Now have canSolve() call canSolve(int patronusRow, int patronusCol), passing in Harry’s location, because that’s where the patronus begins. Then write the 2-argument version of canSolve. This is the trickiest part of the assignment, because this is where the recursion happens. Use lots of print statements and/or the debugger to get this to work. You must print the location of the patronus at the beginning and ending of this function.

You may need to go back to your drawing code to get the breadcrumbs to show up.

Sample run through for the boolean solver:

- Once the boolean solver is working, we can start transitioning our program towards the final version. At this point, you should write code in main() to make the program work more like the examples near the end of this webpage. Specifically, your program should:

- Ask the user for which maze file they want to read.

- Ask the user for the amount of time they want to pause between movements on the canvas (you may want to add an additional instance variable in Maze, and either another method to Maze, or change the constructor so get this value into the Maze class somehow).

- Ask the user if they want to run the boolean solver or the directional solver (you can skip this for now if you want, since the directional solver isn’t written yet).

- Run the solver. You should print out the maze at the beginning and end in text. You should also print out whenever the patronus enters a new square or backtracks (you should already have done this in canSolve()).

- One new part to add is you should keep track of the total number of calls to canSolve that are made, and print this out at the end. You will need to add a new instance variable in Maze to keep track of this.

- Stop and test. At this point you should test your maze solver against the examples in the section below. Verify that the printing of the maze, calls to the patronus entering and backtracking, and the final number of calls matches mine.

Step 5: Get the directional solver working

In this step, we will write the second recursive formulation of the problem, which determines how the maze can be solved. This is done by implementing the functions directionalSolve() and directionalSolve(int patronusRow, int patronusCol). These two functions work similarly so the two canSolve functions. The only major difference is that instead of returning a boolean, they return a string, consisting of directions from the starting location to the cup. Each direction is a character: N (north), S (south), E (east), or W (west).

Write these two functions, following the guidance in the code. The only hard part is changing the code to work with string answers instead of boolean answers.

Sample run through for the directional solver:

Stop and test. At this point you should test your maze solver against the examples in the section below. Verify that the printing of the maze, calls to the patronus entering and backtracking, and the final number of calls matches mine.

Sample output

- maze0: [ Boolean solver ] [ Directional solver ]

- maze1: [ Boolean solver ] [ Directional solver ]

- maze2: [ Boolean solver ] [ Directional solver ]

- maze3: [ Boolean solver ] [ Directional solver ]

- maze3-broken: [ Boolean solver ] [ Directional solver ]

- maze4: [ Boolean solver ] [ Directional solver ]

- maze5: [ Boolean solver ] [ Directional solver ]

Final reminders

Your code should:

- Prompt the user for a filename, pause time, and which solver to use.

- Display the maze textually, run the desired solver, and display the maze again afterwards. The second text maze display should show the final breadcrumbs path.

- As the solver is running, the graphical display should show the breadcrumbs and the patronus as the maze is being explored.

- When done, your program should display the total number of calls to the solver, along with the final path directions and length of the path, if using the directional solver. Meanwhile, in text, it should show the progress of the patronus and the backtracking.

What to turn in

Through Canvas, turn in all your .java files. Additionally, upload a text file answering the following questions:

- What bugs and conceptual difficulties did you encounter? How did you overcome them? What did you learn?

- Describe whatever help (if any) that you received. Don’t include readings, lectures, and exercises, but do include any help from other sources, such as websites or people (including classmates and friends) and attribute them by name.

- Describe any serious problems you encountered while writing the program.

- Did you do any of the challenges (see below)? If so, explain what you did.

- List any other feedback you have. Feel free to provide any feedback on how much you learned from doing the assignment, and whether you enjoyed doing it.

Reminders

- Do not forget to comment your code.

Challenges

- You may notice that all of the sample mazes provided have exactly one solution. That is, there is one path from where Harry starts to the cup. Therefore, your recursive code doesn’t need to handle the situation where it may have to decide which of two possible paths is better/faster/quicker/shorter. Develop a version of your code that will work with mazes with multiple solutions, and find the shortest one. To do this, try copying one of the larger maze files and deleting a few walls. This will open up multiple paths to the solution.